American Clay Artists

Apr 1st - Jun 4th, 1989

American Clay Artists 1989 celebrates the new stature of clay in the old way. It isolates clay to make distinctions and question assumptions rather than to reinforce discriminations about the medium or its disconnection to other artistic expressions. Contemporary ceramic activity is reviewed within a context that has shifted and spread in ways that eradicate some prior opinions and boundaries. Both function and the use of the figure have been redefined by the last two generations of artists using clay. John Roloff transcends these obvious categories and reminds us that clay is but another material for three dimensional art. But the figurative motifs featured here of Arneson (who, like Frey, draws with equal accomplishment and frequently works in bronze), Robert Brady, Jack Earl, Judy Moonelis, Richard Shaw, and Patti Warashina make it clear that clay expresses the human figure as effectively as any other material and perhaps with even greater implicit poetry and metaphor. These figurative artists use clay idiosyncratically and demonstrate no overall unity or cohesive aesthetic; anger, psychic stress, humor, clever conjunction, and sensual fantasy describe some of the different attitudes they explore. Clay's venerable identification with function and the pot has also diffused as one considers the dissimilarities of the vessel-based forms of Christina Bertoni, Jim Makins, Ron Nagle, Adrian Saxe, Chris Staley, Toshiko Takaezu, and Arnie Zimmerman in the works exhibited here. Conventions are repudiated as the vessel form is treated with variegated textures and adjusted in minute or extra large scale. Through complexity and elaboration, function is obscured or completely abandoned. In clay, form no longer must follow function; it symbolizes it or in a current philosophic term "signifies" it. These large and small vessels no longer simply serve to contain, but ruminate more upon the differences between inside and outside and on surface and shape.

Though the community of artists in clay enjoys a degree of loyalty and comradery that is rare within the visual arts, competitiveness and extreme pluralism now prevail, and within it individual talents are now more sharply in focus. The ceramic centers established at Alfred, Bemis, Boulder, Cranbrook, and above all Berkeley, have generated significant academies and coalitions. But, in discussing the evolution of American ceramics, the apostolic legacy of Peter Voulkos is firmly historic, no longer a holy truth. Numerous European artists and now art market-conscious factories must be considered. Several artists who use clay refuse to be in clay surveys, publications, or collections. Many production potters have turned into ceramic sculptors who pursue big prices, commissions, and corporate clients, not the crafts fair passersby or annual studio sales. Many sculptors who use clay now wish to be affiliated with galleries that only represent artists using other media. The folksy repartee of ceramic artists' demonstrations and the team spirit of ceramic artists, so amusingly observed in spirited volleyball games, have been replaced with the realities of individual career development.

The crossover is sufficiently advanced to collapse the differences between art and craft, sculpture and pot. Motives, aesthetics, and ultimately higher prices make craft vs. art of dubious dichotomy. One is left with good and bad art; issues of quality, not category, prevail. Jasper Johns paints George Ohr pots because he enthusiastically collects them. They perform iconographically, and his inclusion of them within his art is a quiet homage to another great southern-born artist. Schnabel's broken crockery speaks of fragmentation and domesticity under siege as effectively as his potent, flat images. Jeff Koons wants to make ultimate commodities, so he turns to a material that attracts by repulsion and asserts class as it negates taste. The surprisingly numerous ceramics of famous modern artists that have been appearing of late in exhibitions and at auctions and galleries elucidate new aspects of these artists, while being their only works that remain economically accessible.

In the hierarchy of fine art, good clay sculpture along with photography, glass, and fiber art, has in the last fifteen years indivisibly joined the rarified realm of painting and sculpture because, in truth, it was already there.

The National Invitational Exhibition

Robert Arneson

Art is Dead

Medium & Materials:

Ceramic, glazed, china painted

Measurements:

64"x19"x19"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Fuller Gross Gallery, San Francisco

Robert Arneson

35 Year Portrait

Medium & Materials:

Ceramic, glazed

Measurements:

76.5"x23.5"25"

Date:

1986-1988

Description:

Courtesy of Fuller Gross Gallery, San Francisco

Christina Bertoni

It Is There Perfected Until Its Last End

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, acrylic paint

Measurements:

6"x17"x17"

Date:

1987

Description:

Collection of the Artist

Courtesy of Victoria Monroe Gallery, New York

Robert Brady

Untitled Figure

Medium & Materials:

Clay, glazed

Measurements:

14"x14"x4"

Date:

1987

Description:

Courtesy Braunstein/Quay Gallery, San Francisco

Jack Earl

In the spring time little light green leaves come quickly out, bright and clean. Then the morning sun turns on its light and they shine and flash. New born, happy little green leaves steal your eyes and mind and they steal your heart.

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, oil paint

Measurements:

32"x18"x16"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy of Perimeter Gallery, Inc., Chicago

Photo: Michael Tropea

James D. Makins

Laocoon

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

16"x20.5"x20.5"

Date:

1989

Description:

Courtesy Barry Rosen Modern & Contemporary Art, New York

James D. Makins

Uptown

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

14.5"x4.5"x4.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Barry Rosen Modern & Contemporary Art, New York

Judy Moonelis

Fold

Medium & Materials:

Ceramic

Measurements:

47"x30"x24"

Date:

1988

Description:

Made possible by the assistance of Watershed Center for the Ceramic Arts, ME

Courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco

Photo: Doug Long

Ron Nagle

Smallest Piece

Medium & Materials:

Ceramic

Measurements:

2.375"x2.25"x1.625"

Date:

1984

Description:

Courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco

Ron Nagle

Orange Bowl

Medium & Materials:

Ceramic

Measurements:

2.75"x4.5"x3.5"

Date:

1984

Description:

Courtesy Rena Bransten Gallery, San Francisco

John Roloff

Ice Orchid/Abandoned Core (Drifting);Dawn, Lake Michigan

Medium & Materials:

Pencil on vellum

Measurements:

36"x72"

Date:

1986

Description:

Courtesy Fuller Gross Gallery, San Francisco

Adrian Saxe

Untitled (Brass Bow)

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, greengold luster, raku

Measurements:

10.25"x9.25"x7.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Garth Clark Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Photo: Tony Cunha

Adrian Saxe

Untitled (Mitosis)

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, gold luster, raku

Measurements:

24.25"x10"x8.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Garth Clark Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Photo: Tony Cunha

Adrian Saxe

Untitled (Red Kamakura)

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, gold luster, raku

Measurements:

12"x9.75"x9"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Gareth Clark Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Photo: Tony Cunha

Richard Shaw

Palette Man

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, decal overglaze

Measurements:

29"x14.5"x10.5"

Date:

1986

Description:

Courtesy Braunstein/Quay Gallery, San Francisco

Richard Shaw

Pink and Grey Book Jar

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, decal overglaze

Measurements:

5"x10"x9"

Date:

1986

Description:

Courtesy Braunstein/Quay Gallery, San Francisco

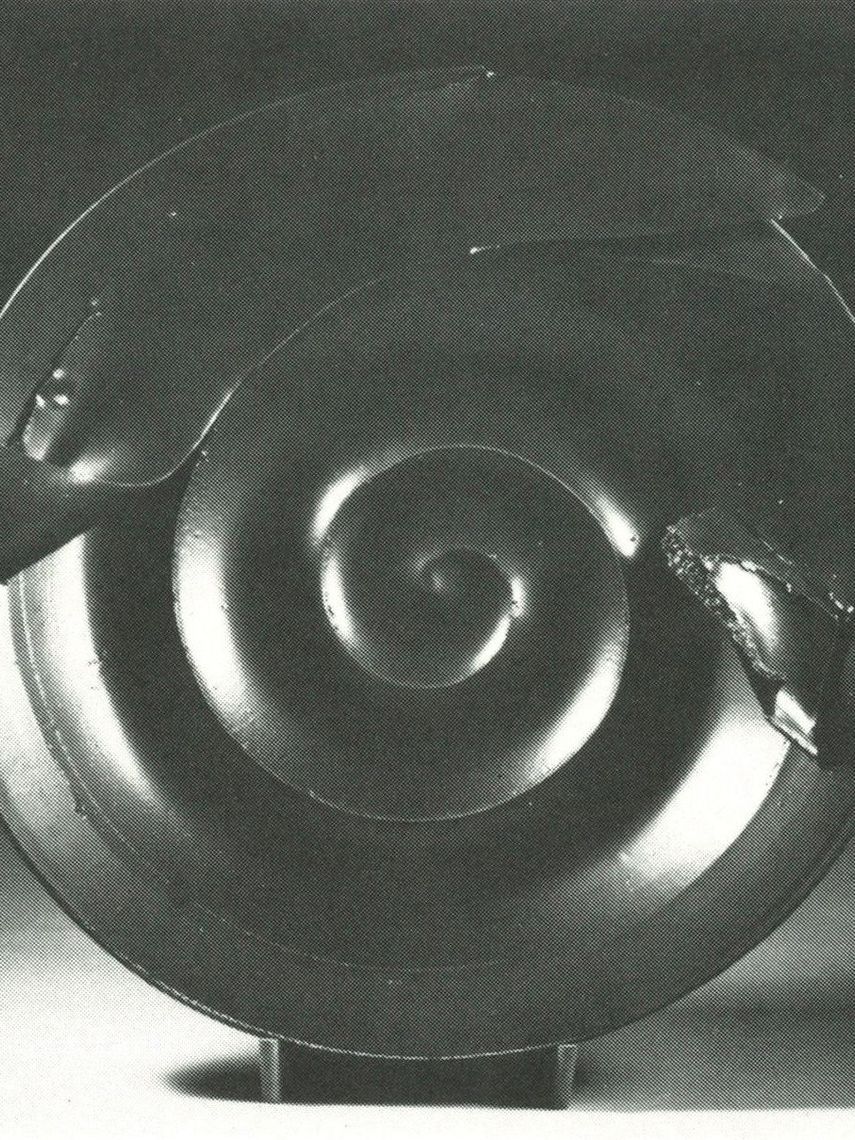

Chris Staley

Black Augered Platter

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

21"x5"x5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Garth Clark Gallery, New York/Los Angeles

Toshiko Takaezu

White Form

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

7.5"x6.75"x6.75"

Date:

1987

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Toshiko Takaezu

Mo-Mo

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

18"x10.5"x10.5"

Date:

1987

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Patti Warashina

Admonishment of the Paint-Taker

Medium & Materials:

Ceramic, mixed media, underglaze

Measurements:

25"x21"x14"

Date:

1988

Patti Warashina

Yellow Ford From the East

Medium & Materials:

1988

Measurements:

21"x39.5"x23.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: Roger Schreiber

Arnold Zimmerman

Reclining Form

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

34"x42"x17"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Objects Gallery, Chicago

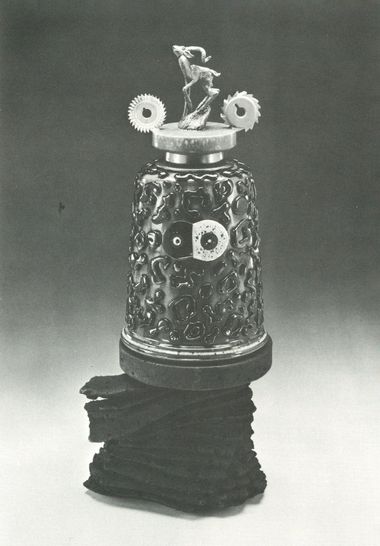

Arnold Zimmerman

Column #1

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

75"x22"x22"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Objects Gallery, Chicago

AMERICAN CLAY ARTISTS 1989: THE SELECTION PROCESS

They say that a camel is a horse designed by committee. Considering what a great animal a camel is, one which in certain circumstances could prove infinitely preferable to a horse, committee design sounds like the way to go. The invited section of American Clay Artists 1989 was put together by a selection committee, and as a member of that committee I believe this exhibition will offer further support for that process.

The selection committee for the American Clay Artists exhibitions, of which this is the third, has always included representation from the various elements that make up the Clay Studio: the board, the advisory board, the resident artists and the executive director. Representing the board are Ann Bora, Georgia Biezup and Ann Wollman, who are collectors and total devotees of the ceramic world. Jill Bonovitz, Bill Daley, Jack Thompson and myself are on the advisory board and, as long-term professional clay-art,ists, represent the core of ceramic activity in Philadelphia. Cate Fetterman and' Betsy Brandt, as resident artists, represent the newer (some may say fresher) professional viewpoint. The executive director of The Clay Studio, Jimmy Clark, is also a professional ceramic artist.

We were a large and diverse group, but we were in absolute accord and committed to reaching our goals: we wanted to select a group of the best artists working in ceramics today, each to be represented by a meaningful body of work; we, wanted the invited artists to reflect the unique range of ceramic activity, which includes utilitarian pottery, sculpture, architectural work, and vessels - the hybrid pottery with metaphor taking priority over function; and we wanted to choose artists who have not recently, if ever, been seen in Philadelphia to any significant degree. These criteria were essentially established in the second exhibition in 1985.

Since it was our intention that American Clay Artists become a continuing series, each exhibition essentially represents a chapter within a long-term saga. The first, in 1983, consisted of 56 artists, each represented by one piece. It was a fine exhibition, giving a large oveNiew of ceramic art work - perfect for the inaugural exhibition, but merely the table of contents at the beginning of a book. The viewer was tantalized but sometimes mystified by the limited representation of each artist's thoughts. There was a need for the meat of the book. In the second exhibition, in 1985, the goal was to give a longer look at each artist; thus 9 smaller group was invited. Spaced three to four years apart, the exhibitions inevitably highlight evolutionary aspects within the discipline. The series has the wholeness of a living organism.

Among the artists in this year's chapter we have seven representing the sculptural aspect of clay work. It is worth noting that all of these artists use subject matter. Robert Arneson, Robert Brady, Jack Earl, Judy Moo_nelis and Patti Warashina work almost exclusively with the figure. Richard Shaw occasionally touches on the figurative but usually lets still life arrangements speak for him. John Roloff has for years used a ship, either in literal or abstract form, as the basis of his work even in his environmental kiln structures.

Jim Makins and Chris Staley are the potters. Jim's pots are usually utilitarian, while the pots made by Chris, though often not totally functional, speak strongly or directly about that origin.

The vessel work in the show uses pottery forms to relate various intellectual or philosophical notions about pots or ourselves. The mark of the hand is one element that Christina Bertoni and Toshiko Takaezu use to illuminate the spirit within their work. Although the mark of the hand is obscured by technique in the works of Ron Nagle and Adrian Saxe, which play off historical tradition of art and pottery, a similar inner spirit is evident throughout.

Among the growing number of clay artists working in architectural scale today Arnie Zimmerman bridges more categories than most. His large, vertical pieces, usually 7 to 8 feet tall, with their deeply carved surfaces speak of monumental sculpture, relief sculpture, and vessels.

Together, the artists represent not only the exciting range of artistic ideas being explored in clay but also a balance of young and established voices. In this way the exhibition continues to epitomize the central role of The Clay Studio which is to help the community grow to understand the truly remarkable nature of artistic expression within the ceramics medium.

Please enjoy.

Ken Vavrek, Professor of Art, Moore College of Art

The Delaware Valley Juried Exhibition

Margery Amdur

Serving Platter with Cup and Saucer

Medium & Materials:

1988

Measurements:

1"x16"x16"

Date:

1988

Ann Batchelor

Time Fragment #2

Medium & Materials:

Clay, oxides

Measurements:

12"x4"x3"

Date:

1988

Description:

2nd Prize: Non-functional

Paul R. Bernhardt

Covered Jar

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

8.5"x6"x6"

Date:

1988

Myrie Borine

Clay Monoprint with 4 Plates

Medium & Materials:

Clay, slips

Measurements:

print: 30"x30"; plates: 1"x12"x12"

Date:

1988

Valerie Bowe

Columnar Series #3

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

19"x10"x10"

Date:

1988

Connie Bracci-McIndoe

Lost Strata

Medium & Materials:

Clay

Measurements:

10"x13.5"x13.5"

Date:

1988

Betsy Brandt

Crayola Urn

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

21"x12"x12"

Date:

1988

Description:

2nd Prize: Functional

Leora Brecher

Hearthstone

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

6.5"x5"x5"

Date:

1988

Alan Burslem

Covered Jar

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

28"x18"x18"

Date:

1988

Peter Collins

San Andreas

Medium & Materials:

Clay

Measurements:

20"x24"x5"

Date:

1987

Description:

Honorable Mention: Non-functional

Carol Cervony

Still Life

Medium & Materials:

Clay, mixed media

Measurements:

32"x21"x19"

Date:

1988

James Chaney

Tea Pot

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

12"x9"x8"

Date:

1988

Jeffrey A. Chapp

Hat Trick

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

24"x16"x8"

Date:

1988

Frank Gaydos

Platter #1

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta

Measurements:

16.5"x16.5"x1.5"

Date:

1988

George Douris

Victory Fragment

Medium & Materials:

Bisque clay

Measurements:

31"x14"x7"

Date:

1980

Judith Golden

Yellow Vase

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

16.5"x12"x9"

Date:

1988

Albert A. Gomez

Ribbon Floor Vase

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

41"x12"x12"

Date:

1988

Janet Grau

Trunks

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

34"x30"x14"; 32"x18"x16"

Date:

1988

Description:

Honorable Mention: Non-functional

Anne Fox Hayes

Garden Table

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware, paint

Measurements:

19.5"x18.75"x18.75"

Date:

1988

Susan Hoy

One

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, nylon

Measurements:

42"x18"x10"

Date:

1988

Dean W. Jensen

Suave Mauve

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, terra sigillata

Measurements:

13"x10"x14"

Date:

1988

Paul M. Jeselskis

Motherload

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware, slip, oxides, residual salt

Measurements:

126"x36"x36"

Date:

1988

David Joy

Anomia Series (V)

Medium & Materials:

Clay, overglaze enamel

Measurements:

18"x18"x2"

Date:

1988

Young A. Kang

Big Casserole

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

8"x16"x16"

Date:

1988

Yah-Wen Kuo

Dream and Memory

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

18.5"x30"x6"

Date:

1988

Paul Leddy

Claw

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

9"x4"x2"

Date:

1988

Beverly Leviner

Amazon Pot

Medium & Materials:

Clay

Measurements:

13"x6"x12.5"

Date:

1988

Beth McGuigan-Turner

Untitled

Medium & Materials:

Clay

Measurements:

20"x16"x4"

Date:

1988

Lynn Meltzer

Platter

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

1"x12.5"x12.5"

Date:

1987

Mitchell John Messina

Bricolage Series #9

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware, paint

Measurements:

58"x8"x6"

Date:

1988

Michael Morgan

Brick Chair

Medium & Materials:

Clay, slip

Measurements:

40"x18"x26"

Date:

1988

Description:

1st Prize: Functional

Richard M. Moyer

Starting to Rust

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

2.875"x12"x12"

Date:

1988

Ann Marie Murray

Bubbles

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

0.5"x10"x10"

Date:

1988

Benjamin Myerov

Storage Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

14"x13.5"x13.5"

Date:

1988

Lis Naples

Fruit Server

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

4.5"25"x9"

Date:

1988

Description:

Honorable Mention: Functional

Lynn Paige

Ceramic Baskets I & II

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta

Measurements:

6"x9"x7"; 6"x11"x8"

Date:

1988

George L. Pearlman

The View

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, underglaze

Measurements:

16"x20"x2"

Date:

1988

Terry Plasket

Jar

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

8.5"x8"x8"

Date:

1988

Dorothy Roschen

Undulations

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, stain, paint

Measurements:

64"x16"x11"

Date:

1988

Amy Sarner

Luminous Footed Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Clay, slip

Measurements:

6"x12.5"x12.5"

Date:

1988

Joan E. Scheckel

I. M. Fast

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, mixed media

Measurements:

15"x9"x7"

Date:

1988

Fran Scott

Green and White Zig-Zag Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Colored porcelain

Measurements:

12.25"x13"x6"

Date:

1988

Lina Shusterman

Vessel Form with Patter

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, slip

Measurements:

24"x9.5"x5"

Date:

1988

Karen Singer

Slice of Life Columns

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, wood

Measurements:

78"x14"x11" each

Date:

1987

Michael Smyser

Texture Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

19"x25.5"x25.5"

Date:

1988

Kenneth Standhardt

Blackware Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Clay

Measurements:

9"x13"x13"

Date:

1988

Description:

Honorable Mention: Functional

Rebecca Tobias

Phoenix Still Life

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, stain, underglaze

Measurements:

14.5"x14.5"x17.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

First Prize: Non-functional

Carol Townsend

Away From Hopi

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, stain, terra sigillata

Measurements:

10"x9"x9"

Date:

1988

Robert Toyakazu Troxell

Sea Dream #3

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

17"x17"x4"

Date:

1988

Dorothy Barclay Weisbord

Untitled

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware, terra sigillata

Measurements:

22.5"x18"x13"

Date:

1988

Helen Weisz

Argil

Medium & Materials:

Colored earthenware

Measurements:

31"x86"x1"

Date:

1988

Natalie Wieters

Decorative Vase

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

15"x12"x3"

Date:

1988

Alan Willoughby

Platter with Floating Shapes

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta, slip, terra sigilatta

Measurements:

26"x26"x4"

Date:

1988

Juror's Statement

The high quality of both functional and non-functional clay pieces reflects both the variety and polish of the contemporary clay world at large as well as the diversity and imaginative reach of the local community of clay artists. In the functional category, artists stretch the limits of function to engage it in a dialogue with its own reality and possibilities. This can be observed in Michael Morgan's Brick Chair which won first prize, and in Betsy Brandt's psuedo-classical Crayola Urn with its celebratory flamboyance. Clay, so quick to catch the unique imprint of individual touch, expresses its full gamut in the non-functional category with pieces as different from each other as Rebecca Tobias's Phoenix Still Life, Ann Batchelor's lyric of coiling in Time Fragment, and Janet Grau's truncated torsos in Trunks. The directions, images, techniques, and poetry are as varied as the individual makers, each object reflecting the philosophic meditations, temperaments, and body rhythms of each maker.

Rose Slivka, Editor-in-Chief, Craft International

Robert Turner, Professor Emeritus, New York State College of Ceramics at Alfred University

The Fifteen Year Clay Studio Retrospective

Judy Axelrod

Untitled

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta

Measurements:

1.5"x16.5"x16.5"

Date:

1987

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Jimmy Clark

Bowl

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

9"x8"x8"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Jill Bonovitz

Large Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, terra sigillata

Measurements:

4"x25"x25"

Date:

1987

Description:

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

Photo: John Carlano

Matthew N. Courtney

Darius Painting on Chama Vase

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta, slip

Measurements:

7"x4"x4"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: Joan Broderick

Elizabeth Dailey

Wallpiece

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta

Measurements:

18"x32"x1.5"

Date:

1987

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

William Daley

Conical Passage

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

16"x26"x26"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

Photo: John Carlano

Nell Hazinski

Platter

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, slip

Measurements:

1.5"x19"x13"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Martha Jackson-Jarvis

Time Gatherers

Medium & Materials:

Clay, copper, wood

Measurements:

30"x36"x18"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtest B. R. Komblatt Gallery, Inc., Washington, DC

Photo: Jarvis Grant

Kirk Magnus

Demon Vase

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

5.5"x8.5"x4.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy The Clay Place, Pittsburgh

Diane Marimow

Rolls in Circles

Medium & Materials:

Colored porcelain, wood

Measurements:

16"x16"x2" each

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Janice Merendino

Untitled

Medium & Materials:

Ink on paper, porcelain, wood

Measurements:

76"x16"x7"

Date:

1986

Description:

Private Collection

Photo: John Carlano

Kevin Dean Mullavey

Olduval

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, stains

Measurements:

19"x44.5"x11"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Kathryn E. Narrow

Fantasy Fish #4

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

2"x16"x12"

Date:

1986

Description:

Located by Judy and Arthur Axelrod

Marian Pritchard

Early Baroque

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, stones

Measurements:

12.5"x6"x4.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Kathie Regan

Plate/Cup/Bowl

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

0.5"x10"x10"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Elyse Saperstein

Spiralled Edge

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta, terra sigillata

Measurements:

67"x13"x9.5"

Date:

1987

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Amy Sarner

Four-Footed Bowl

Medium & Materials:

Clay

Measurements:

6"x8"x8"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Dale Shuffler

Face Vessel

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, oxides, slip

Measurements:

19"x13"x3"

Date:

1988

Description:

Photo: John Carlano

Rudolf Staffel

Light Gatherer

Medium & Materials:

Translucent porcelain

Measurements:

9.25"x6.5"x6.5"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

Lizbeth Stewart

Monkey with Umbrella

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

30"x48"34"

Date:

1986

Description:

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

Photo: Tom Brummett

Jack Thompson

Kangaroo Madonna

Medium & Materials:

Eathernware, stucco

Measurements:

78"x18"53"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Marin Locks Gallery, Philadelphia

Robert Turner

Shore III

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

10.75"x9"x9"

Date:

1987

Description:

Private Collection

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

Ken Vavrek

Monument Valley/Heartbreak Sea

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

7.5"x40"x11"

Date:

1986

Paula Winokur

Ledge: Fore Avebury Site II

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain, sulfates

Measurements:

78"x14"x11"

Date:

1987

Description:

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

Photo: Eric Mitchell

Robert Winokur

Long Table II with Vase

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware, slips

Measurements:

30"x29"x10"

Date:

1988

Description:

Courtesy Helen Drutt Gallery, New York/Philadelphia

David G. Wright

Teapot

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

7.25"x9.5"x7.5"

Date:

1988

In the Spring of 1974, five ceramists - Jill Bonovitz, Janice Merendino, Betty Parisano, Kathie Regan, and Ken Vavrek - pooled their resources and moved into a former spool factory on Orianna Street in the Old City section of Philadelphia. The reasons for coming together were obvious. The equipment, space, and conditions necessary to produce ceramic art are expensive, prohibitive in fact for most artists just starting out. Others looking to work in clay, confronted with the same problems, saw their solution in the Orianna Street studio. The five soon became twelve, and the Clay Studio was born. Initially conceived as a place to work, the Studio began to take on additional functions. Classes were organized and became the key element of an ever-increasing educational mission. The seeds of the present gallery program were planted by the first annual Holiday Show,· when the artists converted their studios into impromptu exhibition spaces. Loosely organized in the earliest days, the potters found that the Studio needed more structure, and a non-profit corporation was formed with a Board of Directors. By 1979, the Clay Studio, now a tax-exempt educational organization, was overflowing its original location. After a lengthy search in the neighborhood of Old City, the artists moved to 112-114 Arch Street in the heat of a Philadelphia summer. Eighteen artists were soon working and teaching at the new site. The excitement over relocating to larger quarters was unfortunately short-lived. The Clay Studio and everything in it was destroyed early one bitter winter morning in 1980 by a fire caused by a faulty heating system. Devastated, the artists regrouped and sought to reestablish the Clay Studio. Support came from the Pennsylvania Council on the Arts and numerous local businesses and organizations includirg Bell of Pennsylvania, Rohm and Haas, Girard Bank, and the Old City Civic Association. Six months later the Studio, fully equipped, was relocated in its present home at 49 North Second Street. A major disaster had been overcome. In the nine years since the fire the Clay Studio has grown into a major arts organization enjoying first regional, then national recognition. The classes have expanded to four semesters annually, servinr some 250 students. Workshops are offered with some of the finest ceramic artists available. The yearly lecture series held at the Philadelphia Museum of Art not only brings to the city major figures in the development of ceramics but confirms our conviction that clay art belongs in main stream institutions. The gallery program has grown to twelve monthly exhibitions per year featuring the work not only of the resident artists but of numerous guest artists as well. The gallery's yearly juried Artist Call attracts close to one hundred applicants from across the country, and the Studio often provides that elusive first solo show for many new clay artists. The Clay Studio has also offered numerous. social programs, either by providing scholarships to disadvantaged youths or by organizing demonstrations and workshops in schools and social centers. Finally, of course, the tri-ennial American Clay

The Clay Studio Resident Artists Exhibition

Susan Arnhold

Dinner Set

Medium & Materials:

Stoneware

Measurements:

1"x11.5"x11.5"

Date:

1988

Betsy Brandt

Minoan Marigold

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

20"x7"x7"

Date:

1988

Cate Fetterman

Blue Table

Medium & Materials:

Colored porcelain

Measurements:

21"x19"x17"

Date:

1989

Anne-Bridget Gary

Anubis Pair/Two Males

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware, porcelain, wood

Measurements:

12.25"x7"x22"

Date:

1989

Yih-Wen Kuo

Autumn

Medium & Materials:

Porcelain

Measurements:

13"x13"x6"

Date:

1988

George L. Pearlman

Alive Blue Movement

Medium & Materials:

Earthenware

Measurements:

60"x30"x3"

Date:

1988

Fran Scott

Striped Vessel with Light Green

Medium & Materials:

Colored Porcelain

Measurements:

12"x11"x6"

Date:

1988

David Shandelman

Soup Set

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta

Measurements:

10"x16"x13"

Date:

1988

Sybille Zeldin

May 28th

Medium & Materials:

Terra-cotta

Measurements:

2"x18"x18"

Date:

1988

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA

Greetings: As Governor, I am pleased to welcome everyone gathered at the Port of History Museum in Philadelphia for the American Clay Artists 1989 exhibition sponsored by The Clay Studio. This impressive exhibit features many of the nation's leading ceramic artists, as well as more than eighty artists from the Delaware Valley.

It is fitting that The Clay Studio, a nonprofit institution dedicated to promoting and encouraging excellence in ceramic arts, is instrumental in presenting American Clay Artists 1989

On behalf of all Pennsylvanians, I welcome you to the American Clay Artists 1989 exhibition, and send my best wishes for the exhibition's· success.

Robert P. Casey, Governor

THE PORT OF HISTORY MUSEUM: CITY OF PHILADELPHIA

Philadelphia supports a thriving crafts community in its galleries, artisans, and collectors which have all grown in number and activity during recent decades. The Clay Studio and its associated artists have played an important role in its resurgence, functioning effectively as a gallery space, resource, and educational center. This success story has attracted support from federal and state agencies and private foundations. The Port of History Museum is pleased to again host a national exhibition showcasing recent clay art, American Clay Artists 1989. The Museum pioneered comprehensive craft exhibits in the sixties and continues this tradition with such recent presentations as American Cloy Artists: Philadelphia '85, Furniture by Philadelphia Woodworkers, New American Gloss, and Turned Objects.

Ronald L. Barber, Museum Director

Sign up for our newsletter.

Stay up to date on all things Clay Studio with announcements, invitations and news delivered straight to your inbox.